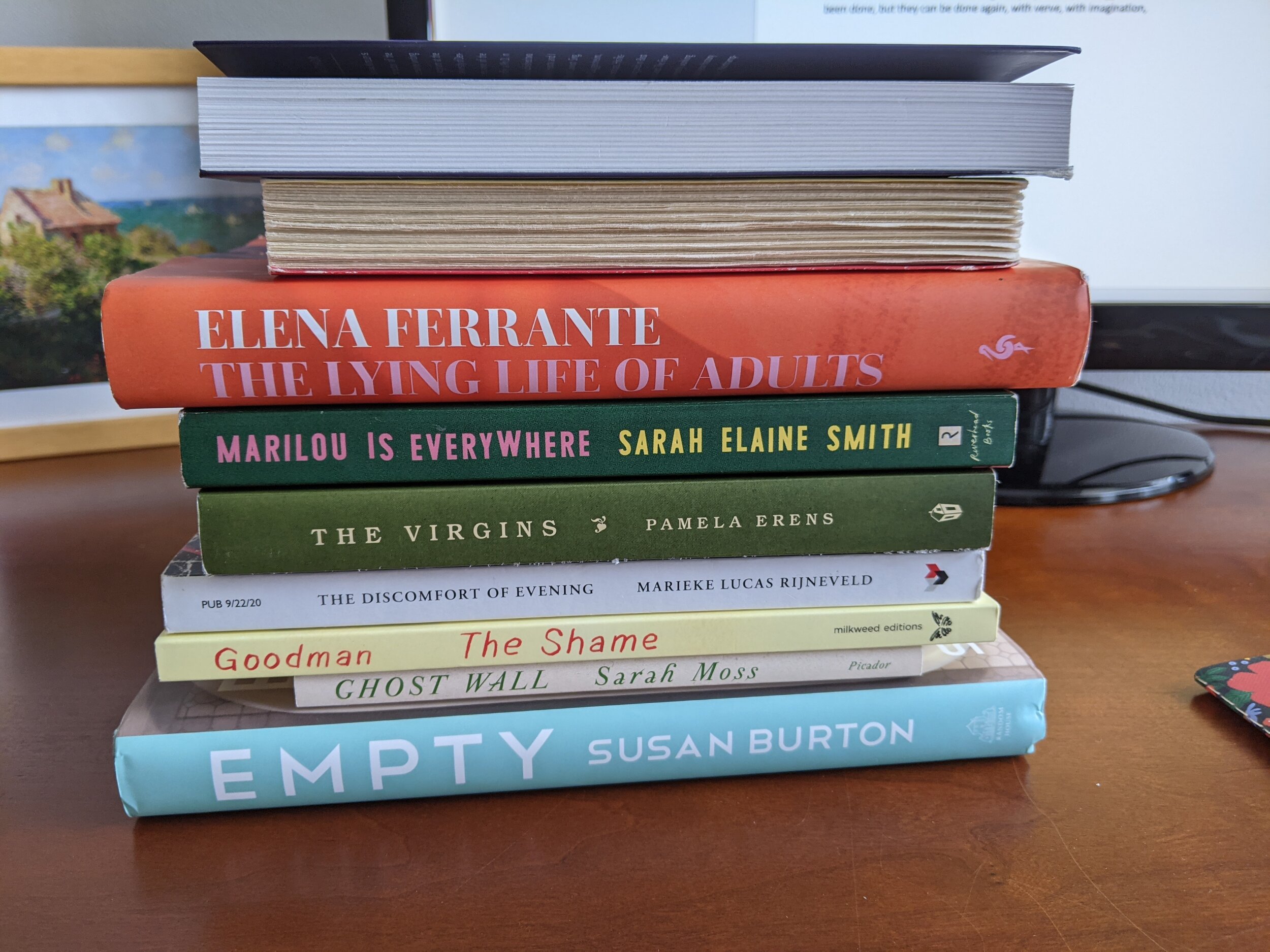

Our favorite books of 2020

Looking for something to read during these fallow, sleepy holiday days? Arshia and Emily rounded up our favorite books of 2020 (note: this list will not necessarily include books that were published in 2020, but books that we happened to read during the year).

Want to buy one or more of these books? Can we recommend Quail Ridge Books, So&So Books, Flyleaf Books, Epilogue Books, Golden Fig Books, or any indie bookstore in your area? Or your local library? And do let us know if you end up reading one of them; we’d love to hear what you think!

Anyway, without further ado, here is our list.

EMILY

Mitko, by Garth Greenwell

Greenwell’s work received a lot of press this year thanks to the publication of his novel Cleanness, but I picked up Mitko at AWP in March shortly before the world shut down and so that’s the Greenwell I read this year. This book is an example of the power of the novella: it’s a tight, controlled study of a psychologically and socially complex relationship between a gay American man and a male prostitute in Sofia, Bulgaria. Come for the intriguing power dynamic; stay for the fresh, delicately rendered setting (I spent a lot of time this year sating my desire for international travel by soaking up the details of foreign cities through books). I considered putting 2020’s Swimming in the Dark on this list instead of Mitko, as both tell similar stories of taboo queer love in the Eastern bloc, but ultimately, although Swimming After Dark made Communist Poland come alive on the page, I was more intrigued by the complexities of the relationship in Greenwell’s work.

The Illness Lesson, by Clare Beams

I absolutely loved Beams’ short story collection, We Show What We Have Learned and Other Stories, so I couldn’t wait to pick up her first novel, and it did not disappoint. It hit so many of my readerly interest buttons: New England, the 19th century, weird historical fiction that’s more concerned with strangeness than accuracy, strange illnesses, girls, schools, disgruntled and repressed women. The writing, setting, and language were all gorgeous, and the feminist themes didn’t hurt, either. (here’s your weekly reminder that Beams is one of the three judges for our first-ever writing prize, so you should definitely read her book and then enter the contest!).

Uncanny Valley, by Anna Weiner

This book is a perfect example of what, for me, makes a great memoir: the personal story and the broader social milieu are rendered in equally exquisite detail and are equally compelling. Uncanny Valley follows Weiner as she leaves the “shabby glamour” of New York publishing and takes a tech job in San Francisco. As an artsy millennial, I felt seen by this book: it dissected my generation in thought-provoking, clever prose, while also dissecting the culture of a place that we should all be scrutinizing if we want to understand our society’s rapid changes. Plus, Weiner is just a fabulous writer: her details and sentences are devastating in their observational accuracy.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, by Ocean Vuong

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is written in the form of a letter to the narrator’s mother, a refugee from the Vietnam War eking out a living in Hartford, Connecticut. I resisted Vuong’s book last year because I was afraid it wouldn’t be narrative enough for me, but I’m so glad I took the plunge: I read this in a day, swept away by the short sections, the brutal emotional honesty, and the complex relationships between the narrator and his mother, the narrator and New England, the narrator and Vietnam, the narrator and Trevor, a local boy who becomes his best friend and lover—really, the narrator and everyone. I also loved seeing my native New England refracted through this experience deeply different than mine—seeing the familiar in a new way, from a new perspective.

Go, Went, Gone, by Jenny Erpenbeck

As a Berlinophile, I’d been eager to pick up Erpenbeck’s works for awhile, and this year, I finally found my way to this story of a retired German university professor who befriends a group of refugees living in a home nearby. It’s not cheesy at all, I promise: instead it grapples with questions of the power and limit of identification between people who’ve suffered different traumas, and questions of how much a human being can and should endure. I’m also biased towards this one because of how clearly and cleanly Erpenbeck’s writing conjures up Berlin and its environs. Once again, traveling through books.

Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy

If you had me as an instructor this spring, you probably heard my spiel about how revisiting classics as an adult can transform your experience of said classics—a spiel inspired by my re-read of Tolstoy’s tome (and by my reread of Madame Bovary a few years ago). When I read this book in high school, I was dazzled by all the drama on skating rinks, but, having not yet experienced much of life, I did not understand any of the emotions. At 31, reading a much better translation, I suddenly understood Anna’s grand desires and humiliations, the little barbs the characters lob at each other and the joys they share. This wasn’t an easy read, but I felt enriched when I was done, and it’s a reminder that just because you read a book when you were a teenager—did you really read it?

Fever Dream, by Samanta Schweblin

I read this book in one sitting in a bathtub. It did not do wonders for my anxiety, but I include it here because of the skill on display: in this story about a family that goes on vacation in the Argentinian countryside and starts encountering Strange People and Uncanny Things, Schweblin conjures dread through the most innocuous-seeming image. This book evokes that feeling of second-guessing yourself when you’re trying to figure out if you’re just being paranoid or if something is very, very wrong. It’s also about environmentalism! Read this if you want to understand atmosphere, dread, and how to use a claustrophobic narrative and setting to conjure up both of those.

A Burning, by Megha Majumdar

Too often, I read books where the interpersonal drama or the characters’ choices feel forced, not inevitable. That’s why I loved A Burning: it’s about the train wreck of a situation that main character Jivan finds herself in after being wrongfully accused of plotting a terrorist attack at a train station in Kolkata, and the failure of the system and those around her to protect her or even to care that they have the wrong girl. The characters’ choices and actions feel earned to me; the tragedy unfolds and it feels inevitable, even though you don’t want it to. Besides, it’s about systems failing and people prioritizing their own ambitions or needs over the good of others, which, you know, 2020.

Little Weirds, by Jenny Slate

I knew Slate from her role in Parks and Recreation and not much else—until, on the recommendation of a friend, I picked up this memoir. The story is conventional: Slate is trying to get over her divorce, trying to be okay again. But the memoir is anything but conventional. Told in that short-section style that’s so popular these days, the book jumps from weird image to weird idea, using Slate’s hallucinogenic imagination and particular aesthetic style to shepherd us along on her journey of healing. I highly recommend this as an example of fearless writing and of how to embrace your own singular brain, and not fear unconventionality, when you’re telling your story.

ARSHIA

The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante

When Ferrante first became immensely popular in the US, around 2015, I knew nothing about her books, but I eschewed them because they were popular. (I know, right, I’m so cool?) After some time, starting with her darkly glorious masterpiece, Days of Abandonment, I rectified my folly and am now am a Ferrante stan. The Lying Life of Adults follows in the great Ferrante tradition: it is an intensely interior book about a teenage girl in Naples named Giovanna who is struggling to find her place in the world. I felt deeply for Giovanna as she encountered troublesome parents and relatives, friends, and love interests and stopped only to marvel at Ferrante’s skill at charting the shifting inner lives of girls and women. If you haven’t read any Ferrante yet, I implore you—stop what you are doing and read her now!

Marylou is Everywhere by Sarah Elaine Smith

You know that feeling when you read the first few sentences of a book and just know that you are in for a treat? That is how I felt upon opening Smith’s Marylou. Take, for example, this second paragraph—it is the perfect introduction to the protagonist’s, fourteen-year-old Cindy, disconsolate existence and it makes you understand why she behaves the way she does as things begin to spin out of control later on in the book:

I did not care for the real. It didn’t seem so special to me, whatever communion I could take with the dust spangles, or the snakes that spun in an oiled way along the rotting tractors tires stacked up by the shed, or the stony light that fell in those hills and made the vines and mosses this vivid nightmare green. None of it had a purpose to me. Everything I saw seemed to have been emptied out and left there humming…My life was an empty place. From where I stood, it seared on with a blank and merciless light. All dust and no song. Rainbows in oil puddles. Bug bites hatched with a curved X from my fingernails. Donald Ducks orange juice in a can.

With a less skilled author, this might just have been beautiful writing, but Smith sustains this captivating combination of lyricism and specificity for the duration. By happenstance, I read this book in the mountains, which mirrored the intensely rural landscape of Cindy Stoat’s life. So if you find yourself on a mountain with nothing to do, read this book!

The Shame by Makenna Goodman

This book hits all my pleasure buttons: domestic malaise; obsession; quiet discontent; a narrator slowly yet precipitously sliding out of control, and mystery (the mystery of why mother and wife Alma is in her car, driving away from her husband and children.) It even manages to do what I have come to think of as standbys for suburban discontent—a dinner party of academics where things invariably go away—in a way that is engaging and funny. As Jenny Offill says, Goodman’s “depiction of the longing, self-loathing, and quiet rage that accompany sidelined ambition is brilliantly complex.”

Death in Her Hands by Ottessa Moshfegh

Lonely, obsessive older woman tries to solve self-generated mystery to dark and, at times, hilarious results might be the headline if this book were a news article and this particular newspaper had a very bad editor. Kevin Power says it beautifully in his New Yorker review: “Death in Her Hands is the work of a writer who is, like Henry James or Vladimir Nabokov, touched by both genius and cruelty. Cruelty, so deplorable in life, is for novelists a seriously underrated virtue. Like a surgeon, or a serial killer, Moshfegh flenses her characters, and her readers, until all that’s left is a void. It’s the amused contemplation of that void that gives rise to the dark exhilaration of her work—its wayward beauty, its comedy, and its horror.”

The Virgins by Pamela Erens

Set in a New England prep school, this novel distinguishes itself because the narrator, Bruce, is a student at the school who intently and creepily watches the main character, Aviva, and her boyfriend, Seung. The New York Observer writes, “Perhaps it is going too far to say that The Virgins is primarily about the fundamental flows of white, male narrators in fiction,” but I agree that this novel brilliantly and obliquely reveals these shortcomings. It is also a novel about sex and power, and it is immensely gripping.

Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss

From an NPR review: “Ghost Wall is such a weird and distinctive story: It could be labeled a supernatural tale, a coming-of-age chronicle, even a timely meditation on the various meanings of walls themselves. All this, packed into a beautifully written story of 130 pages. No wonder I read it twice within one week.” It is all this and more. The premise is fascinating: seventeen-year-old Silvie is forced to camp with her father, a man obsessed with Iron Age Britons, and some graduate students and their professor. The threat of violence hangs like a dark cloud over the landscape. Silvie navigates this treacherous terrain with her deep knowledge of the natural world and her keen observations about the social dynamics around her. Somehow, this book manages to tell us the deeply personal tale of Silvie while also interrogating the dangers of masculinity and nativism.

Empty by Susan Barton (a memoir)

I will admit I was skeptical when I read a review about this book. Sigh, I thought, another memoir by an affluent white woman. But because I was procrastinating doing other work (relatable), I read an excerpt and was instantly hooked by the clean, economical prose and the intimate struggle of a precocious teenage girl. Burton’s younger self is tightly wound, smart, and stubborn, and in the first chapters, the growing pains of getting her first period, shaving, and clashing with her parents are heartbreakingly rendered. Jill Ciment writes, “Burton has sidestepped cliches, and captured the enigma of attempting to sate, by gluttony and starvation, our human vulnerabilities.”

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

What can I say about this book that hasn’t already been said? It is dark, claustrophobic, weird, creepy, and glorious. After I finished, I felt a deep sense of loss and googled, in vain, “books like we have always lived in the castle” before starting it again. Merricat, with her affinity for “deathcup mushrooms” and magic, and who lives with her older sister Constance in near isolation in a large, run-down house, is such a distinctive and uniquely specific character. But don’t take my word for it—here is how the book opens:

My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on. Both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the deathcup mushroom. Everyone else in my family is dead.

With a cliffhanger like that, what are you waiting for?

The Discomfort of Evening Marieke Lucas Rijneveld

Winner of the 2020 Booker Prize, this book gives me Ian McEwan’s The Cement Garden or Richard Hughes A High Wind in Jamaica vibes in that it is about children becoming increasingly feral without the supervision of their parents. Ten-year-old Jas is a confused, anxious girl growing up with her super religious parents and siblings on a dairy farm in the Netherlands. “I predict you will love this book,” Emily said as she loaned it to me, and she was right. It is a dark tale (are we noticing a theme here?), about childhood, fear, shame, loneliness, and grief. The Star Tribune writes, “One judge described ‘The Discomfort of Evening’ as ‘a tender and visceral evocation of a childhood caught between shame and salvation,’” although the author of the review had a hard time locating the “tenderness and salvation.” For me, the tenderness in not in Jas’ life circumstances so much in the care that Rijneveld takes in articulating the particularities of Jas’ plight.

***

Arshia: My takeaways from this list? The old can be made new—domestic ennui, the cloistered environment of a new England prep school, a struggle with anorexia, teenage girlhood—these have been done and done, but they can be done again, with verve and imagination, to gripping results. So as 2021 looms, read on and write on!

Emily: My takeaways? Arshia stole a lot of the books that I was going to write about—we have similar taste! But more seriously, books represented an escape for me this year, a way to soak up other places, other minds, other situations, or to reflect back, in a new way, a place or situation I know well. As the new year dawns, remember that by writing, you can and should achieve this sensation for your readers and perhaps for yourself. So, with that battle cry, take to the Word documents and write on!

Happy 2021!

Arshia and Emily